On 1 April 2020 Peter Hobson, for over a quarter of a century one of the most important figures in British fencing, died from the complications of a 2015 operation. He was 87.

His influence extended everywhere in the sport, although his main contribution was as an official, referee, and administrator. He was a fine fencer, coming third in the Junior Foil in 1961 and that same year also third, after a three-way barrage, in the Corble Cup; ten years later (having lost five years of fencing due to a recurring elbow injury) he was again in the Corble final, coming second to the Bulgarian professional George Ganchev. In 1962 he was a member of the Polytechnic squad that won the sabre team championship. His widow Jill recalls that he would have liked to have won a major title, but “found it difficult to win in deciding fights and used to joke about never being able to beat Ganchev, partly because George was so tall.”

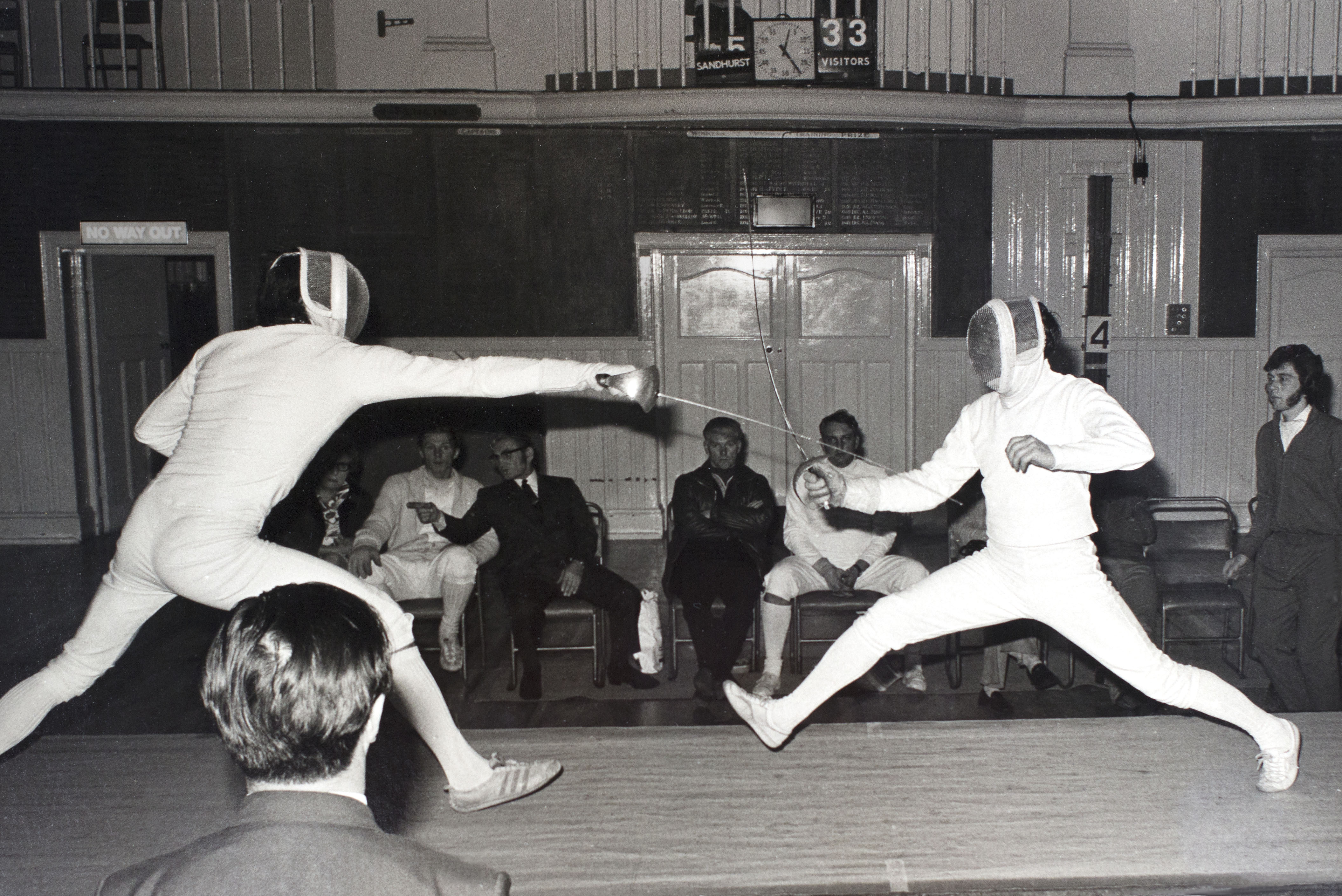

Peter Hobson (R) with what looks like a perfect countertime action against George Ganchev (L) in the Corble Cup, 1971, when he finished second to Ganchev, his best international result.

By the time he accepted his Corble silver Peter was already involved in running the sport. In 1971 he became chair of the sabre sub-committee, a selector and captain of the sabre team at the world championships; the following year he was overall team captain for the Olympic Games, a bitter-sweet appointment given the appalling tragedy of the Israeli killings. In 1973 he was elected vice-chair of the AFA Committee and chair of the joint weapons sub-committee, positions he held until 1996, and for ten years represented fencing on the British Olympic Committee (where Princess Anne, whom he rated as superbly efficient, was chair). In 1979 he became a vice-president of the AFA; as his friend Mary Glen Haig was president, he could hardly have risen higher.

An international referee, he presided over the finals of all the major British national and international competitions as well as at junior and senior world championships, the Commonwealth Games and other international events. He was a qualified foil and sabre coach. Hugely competent in all these positions and hugely liked, he was at the heart of fencing and helped it to beat more efficiently. And he was far from being just an able lieutenant: old copies of The Sword have him as a frequent contributor, sounding off authoritatively at un-thought-out attempts by the FIE to reform the rules of fencing or on one occasion memorably defending the sabre team against a charge of irresponsibility at the 1974 world championships.

Generally, though, he kept his emotions very much in check. John Deanfield, a regular sabre team member between 1970 and 1980 and national champion in 1975, recalls him as “very English – you had to dig under the skin to know what he was feeling. But he was like a big brother to me: whenever I saw him again it was just where we left off the last time – it was lovely.”

Peter was born in Stoke Newington, North London, on 19 May 1932, to a dressmaker and master tailor. At the age of six he developed asthma, and as it grew progressively worse had to inject himself with a personalized vaccine. This affected his ability to attend normal school activities until he was about fifteen. He then contracted scarlet fever and spent six weeks in isolation – one significant bonus being that his asthma faded away.

After school at Enfield Technical College, he completed two years in the Royal Air Force before enrolling at Shoreditch College (part of London university) to study design and technology, planning to become a teacher. As a teenager he had taken up photography, and Shoreditch had a well-equipped darkroom, as well as a very good fencing club.

He was an avid reader, notably authors such as Ransome, Dumas, Hope and Rafael Sabatini. Many of the novels featured deeds of swordsmanship and one in particular, The Fencing Master by Sabatini, captivated him. Neither of his parents had been keen on sport, nor his one sibling, his sister Ann, but Peter had started fencing while doing national service. “Like almost every other fencer I come across,” he wrote in an article in The Sword in 1971, “I started to fence with the foil; I was the typical product of National Training in this respect. At some point in my career someone said, ‘To get anywhere in this country you have to fence two weapons,’ so I purchased an epee. Three lessons and the Junior Epee later, I was convinced that I didn’t like that game, and I turned to sabre.” He learned initially under Professor Alf Simmonds in East London, then Professor Walter “Killer Nick” Nicklen, who at Merchant Taylors School tutored such internationals as Sandy Leckie, Peter Jacobs, and John Rayden. As his involvement in fencing increased, he became a protégé of Charles de Beaumont, longtime head of the AFA, joining him in public exhibitions where de Beaumont would have at him with a gigantic two-handed sword.

Peter eventually moved to the Regent Street Polytechnic (then the largest club in the country), taking on a new coach, the Hungarian émigré Bela Imregi. The two became close and used to talk to each other in Béla-ese; Peter came to use many of the stubborn Hungarian’s idioms. The “hole in head man,” for example, was Béla’s phrase for one of the British team’s most illustrious members, who had a bald spot. Armed with Béla’s letters of introduction, Peter would visit the illustrious Honved club in Budapest, and also schools in that city – even attending, to his delight, a class where they had “English joke time.”

In 1954, Peter had joined Joseph Priestley Technical School, based in Hackney. Six years later, he was appointed a housemaster at the brand-new Brooke House Boys comprehensive in Hackney, a deprived north London borough with a high immigrant population. Peter coached fencing and boxing, organized football and cricket teams, and took part in summer camps, trips to the Lake District and North Wales, as well as to Switzerland and Italy for skiing. He was also happy to help anyone who shared his other great passion, photography. “Over the years,” says Jill, “his favourite subjects were motor racing, big cats, raptors, almost any wildlife, and cathedrals.” Even so, his iconic photographs of fencing, many published in The Sword, are among the best ever taken of the sport. He won many awards, and several of his photos have appeared in national newspapers.

At his previous school Peter had started up a fencing club (as he later confessed, for foilists only) and even a boxing club, his charges notching up a stream of successes, a silver medal in the London schoolboys foil and at boxing all the district team trophies and two national championships in a single year. In 1969 he organized a junior training scheme at sabre under the auspices of the CCPR. At Brooke House, he successfully introduced pupils directly to sabre and argued forcefully for the extension of proficiency awards to that weapon and to epee. The school’s fencing team, the first and only such in a state comprehensive, was soon producing three national schoolboy sabre champions and several members of the English Schools fencing team. To Peter’s carefully masked delight, the boys frequently beat teams from public schools and even the Royal Navy. Next he persuaded Béla Imregi to coach his eager young recruits – on his otherwise only afternoon off. Two Brooke House boys were the first in the country to receive the gold proficiency sabre award, while another was runner-up in the London schoolboys championships. Yet greater achievements followed, all within a four-year span. “I had proved, to my own satisfaction at least, that boys found sabre an easier weapon to come to terms with than foil.” He ends his article by naughtily quoting a first-year fencer who by accident saw a foil. “What a funny sword – looks all sort of weedy – what’s it for?”

# # #

In 1971, at Peter’s instigation, I went to teach English at Brooke House and saw his skills at first hand. He had a number of mannerisms, thus would tilt his chin to the left and slightly raise his head, setting his lips tightly together as if detecting a slightly unpleasant smell; this had the effect of imparting great authority. He went on to become deputy head, then in 1975 headmaster. In that role, he taught every first-year class so he would know the names of all 1,200 pupils.

One of them was Geoff Thompson, who was to become a multiple karate medal-winner internationally, including the 1982 world championships. In 1995 Thompson was awarded an MBE for being Britain’s first leading Afro-Caribbean sports administrator. He credits Peter with saving him from a life of delinquency. “He was one of those teachers who stood out by the sheer presence of his personality and the way he managed to engage with different boys in different ways,” Thompson wrote in a eulogy, and added: “He was the most feared housemaster of Brooke House because his fencing wrist and technique clearly translated into the then discipline of caning.” Boys commented that “he doesn’t need to take a big swing or run up, but he does the most damage.” Peter also wore Mohair suits along with brown suede Hushpuppies, which for all the Afro-Caribbean boys made him a fashion icon, “the slickest dressed housemaster of the school.”

Fancy dresser he might have been, but to both the pupils and the staff he seemed the epitome of a confirmed bachelor. It was while serving as deputy head that he interviewed his future wife Jill Wise for a post at the school. Before she applied, an adviser at the Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) told her there was a “difficult” deputy head at the school she was applying to, who didn’t suffer fools gladly. Was she any good at photography? Luckily, she was. “Although I’d been a teacher previously (of geography, the same as Peter) I’d re-trained as a media resources officer, and this was close to his heart.” She got the job.

Peter wooed the pretty new staff member by bringing his tape recorder into school to play the third movement of the Sibelius Violin Concerto to encourage her to go to a concert with him. Not surprisingly, it became a special piece of music for them. Eventually he summoned up the courage to propose, but did so in a characteristically offhand way, one afternoon asking, “How much do we annoy one another?” It took her several days to realize what he was getting at.

They were married in 1977 (complete with jokes from the registrar about Hobson’s Choice) and moved to Enfield, first to a flat then a townhouse overlooking one of the MCC cricket grounds. Peter’s list of enthusiasms make it incredible that all this time he was doing so much for fencing. Besides his chosen sport – and his photography — his passions, followed lifelong, included music (he was a hi-fi expert) and fast cars. In the summer of 1971 he drove me all the way from London to Vienna (915 miles) — for the world championships —managing it in a day. In addition, he had a keen interest in motorbikes (over the years owning two BSAs and two Nortons) and his cars included Lotus Cortinas Mk 1 and Mk 2, an Alfa Romeo Alfetta, and two AUDI TTs. He was a long-time member of the British Automobile Racing Club and regularly attended Grand Prix and other international events.

He was also a keen cyclist, while he enjoyed climbing, walking and skiing, and he and Jill often spent holidays walking in the Lake District, Dartmoor and the Peak District. He made and bought car models, as a youngster making display models for a local shop that funded his first racing bike, and this hobby too continued in later life. Well into middle age, he took up horse riding, despite a deep mistrust of the animal, as it was such a passion of his wife’s. He soon discovered that it was a technical sport, like fencing, and so appreciated the skills involved much more.

Peter joining forces with an all-international team (once!) of John Rayden, George Birks and Brian Howes, turning out for the Polytechnic at the Magrini Cup in the late 1970s

In 1982 Peter moved to be head of the London Nautical School, where the students did nautical studies as well as the normal comprehensive school curriculum. The school had a fleet of boats, kept at one of the London docks, of which Peter was the “captain superintendent.” After five years at LNS he became full-time general secretary of the London area of the Secondary Heads Association, and an elected member of ILEA’s Education Committee. In 1990 the ILEA was abolished; Peter chose early retirement and joined the non-teaching staff of a Barnet school as computer systems manager.

He took up fencing again in his late sixties when he discovered a local group, and was teaching at the Dacorum Fencing Club in Hemel Hempstead until he was about 80, when ill health forced a final retirement. By then, he and Jill had moved to a house near St. Albans, with an attractive garden, and a pond to encourage the wildlife of which Peter was so fond.

For the last eight years, Peter’s deteriorating health limited his mobility, although he did have a talk he gave to various local photography clubs, “Fencing, Photography and the Olympics.” (One wonders whether, while reminiscing about the atmosphere at the opening ceremony in Munich in 1972, he finally admitted to smuggling in a Minox camera secreted in his blazer pocket, as cameras weren’t allowed for participants.) The last time he was able to go anywhere significant was to see the men’s sabre team finals at the London 2012 Olympics. Three years later he had a major operation, and he had further episodes of ill health, culminating in his being admitted to hospital at the end of March 2020 for emergency surgery. Although he came through the operation, he deteriorated rapidly and didn’t recover.

With his kind and considerate nature, but with the necessary authority and charisma to make him an excellent head teacher and respected sports official and leader, he was genuinely loved. Words like modesty, fairness, reasonableness, reticence all come to mind, together with memories of his dry sense of humour. His marriage to Jill was a source of joy: they were the best of friends, and soulmates too. Lucky them; lucky us.

Kindly provided by Richard Cohen. For all enquiries relating to this article please contact [email protected]

Sign up to receive regular highlights from the exciting world of fencing - celebrating the best of our unique and inspiring community